Robert Macdonald painted the picture below, ‘Falling Airman’, in 1978 when he was a mature student in the Painting School of the Royal College of Art, London. Looking back to his childhood years, he embarked on a series of paintings at the RCA which explored feelings related to the Second World War. He was born in 1935 and in 1942 he was in his family home when it was destroyed in a German bombing raid. Much of his early work as a painter was overshadowed by war-time and post-war upheaval.

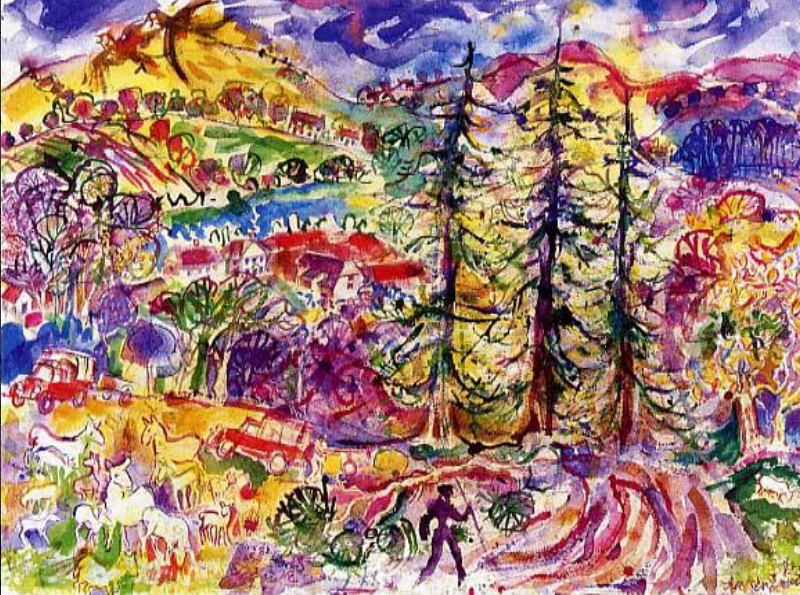

His painting underwent a sea change in the 1990s when he took over an isolated cottage in the Welsh hills and for the first time began to meditate as an artist on his immediate surroundings. Since then he has become known for his landscapes of the Usk Valley and the Brecon Beacons, and his pictures of the farming life and the legends of that area.

His past still intrudes. In 2013 he took part in a project, run by the Swansea Print Workshop, to commemorate the Dylan Thomas centenary and celebrate the poet’s connections with Swansea. Macdonald chose to focus on the poet’s prose work written for radio, ‘Return Journey’. Thomas wrote about returning to Swansea after the Blitz, attempting to reconnect with his early self while walking through the ruins of the destroyed city. Macdonald’s etchings present the poet amid the ruins, with ghosts of German aircraft still in the sky overhead.

Robert’s move to the Welsh hills was in a way a return to his rural roots. He was born in Spilsby, Lincolnshire, son of a rural veterinary surgeon who gave up his profession during the war to work as a radar technician in a heavily militarised area of the South Coast. After their home was bombed he and his siblings were scattered as evacuees, Robert spending the rest of the war in Somerset where he lived for a time on a farm He was sent to a small boarding school for a time, but ran away from it twice. Before the war ended his father returned to veterinary medicine and was offered a job in the far north of New Zealand. He became the first vet sent to that part of the north, and after the Pacific war ended the rest of the family sailed from Liverpool to join him, arriving in 1946 to come together as a family again for the first time for almost four years.

They found themselves in a mixed community of Maori and Pakeha (white people) including many of Highland Scots descent who had settled that part of the north in the mid-19th Century. Robert’s father was known as a brilliant professional and came to represent all the country’s vets on the New Zealand Veterinary Services Council, but he also suffered a long battle with alcoholism which cast a cloud over the children during their later school years. Although he dreamed of painting, there was no prospect of going to art college when Robert left school, and he joined a small country newspaper as a cadet reporter, later moving to work for New Zealand’s largest paper, the Auckland-based Herald. While in the Herald’s branch office in the Waikato city of Hamilton, he began painting in his spare time and became a committee member of the Waikato Society of Arts, helping to run the society’s small art gallery. At this time fierce controversies raged in the country over the arrival of Modernist exhibitions from overseas. Robert was drawn into these excitements both as a painter and a journalist, writing reviews in the Waikato Times defending Henry Moore and Picasso. He got to know artists such as Colin McCahon who in later years were to become famed figures of Antipodean Modernism.

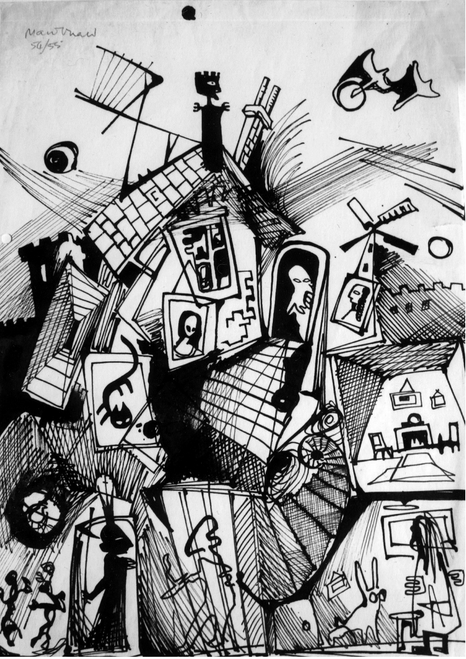

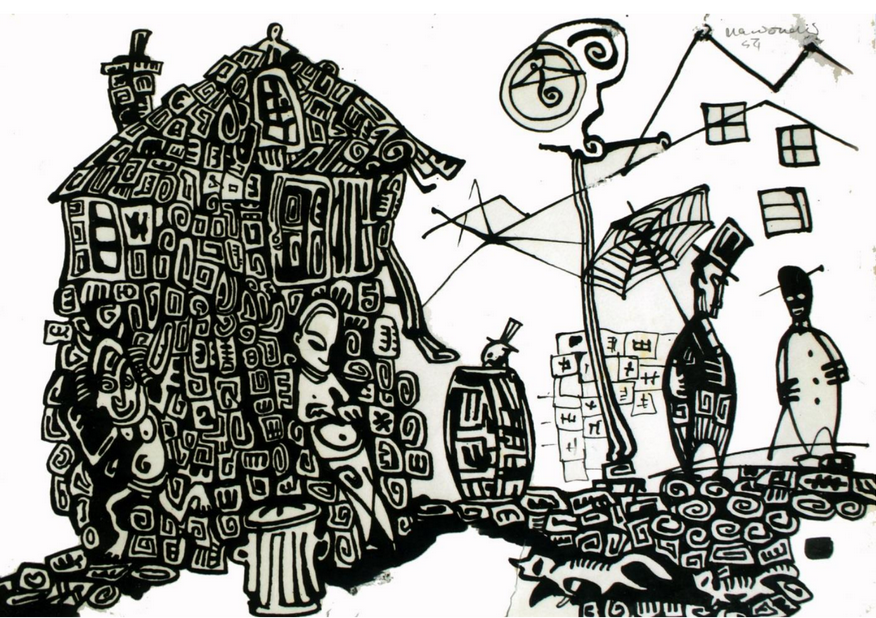

As a teenage would-be artist he was influenced by Paul Klee’s advice to ‘take a line for a walk’, and many of his earliest pictures done in Indian ink are extended doodles in which unwittingly he began to explore his own rather overstocked unconscious. He knew nothing then of Freudian or Jungian theories. Only in later years did he recognise in these works symbolic images of his childhood upheavals, including the picture below of an exploded house.

In Britain in the early 1940’s, when there were air raid warnings, Robert and his siblings would crouch under their desks at school until the All Clear sounded, and at night they were taken downstairs to lie like sardines under their kitchen table. Early one morning a stick of bombs fell on their street and there was no warning. Although its windows, doors and ceilings were blown in and the walls were cracked, the Macdonald residence remained standing while their neighbours’ houses collapsed, and Robert’s first memory is of his father emerging through a cloud of plaster dust to carry him downstairs over a sea of broken glass. In this picture there is a staircase winding downwards past exposed rooms and ghostly figures. The drawing alongside it is of a house of cards, drawn with Polynesian patterning.

He was sacked from the Herald in 1958 for growing a beard, and left New Zealand in March of that year as a crew member of a small sailing ship. Arriving in Australia he travelled to Italy on a returning Italian immigrant ship, made his way overland to Britain and was accepted as a student by the London Central School of Arts and Crafts. Having spent his first year as a cadet reporter in the press room of the Waikato Independent, pulling proofs from galleys and surrounded by presses and inky printers, Robert was immediately at home in the Central’s etching workshop, and his first etchings gained him remarkably quick success. The American Abstract Expressionists were arriving in Britain. He went with other Central students to the first showing of Jackson Pollock’s paintings in the Whitechapel Gallery, and returned to the Central to create ‘Mounted Knight’, the picture below using flung sugar-lift.

Obviously influenced both by Picasso and by Pollock. ‘Mounted Knight’ may have been the first work exhibited in London showing Pollock’s impact, and was included in a touring exhibition, ‘Twenty-five British Printmakers’, sent to South America by the St. George Gallery in Cork Street. Macdonald was the only unknown among a collection of printmakers including Sutherland and Piper. Having no grant to sustain his studies, he ran out of money and had to find a job in a hurry. Soon he was working as a journalist again, in Fleet Street. He wrote on foreign affairs and African nationalism for the London office of The Scotsman and was for a time their theatre and arts critic in London. Throughout this period in the 1960s he continued to paint in his spare time, creating pictures like this doom-filled image of Fleet Street (below).

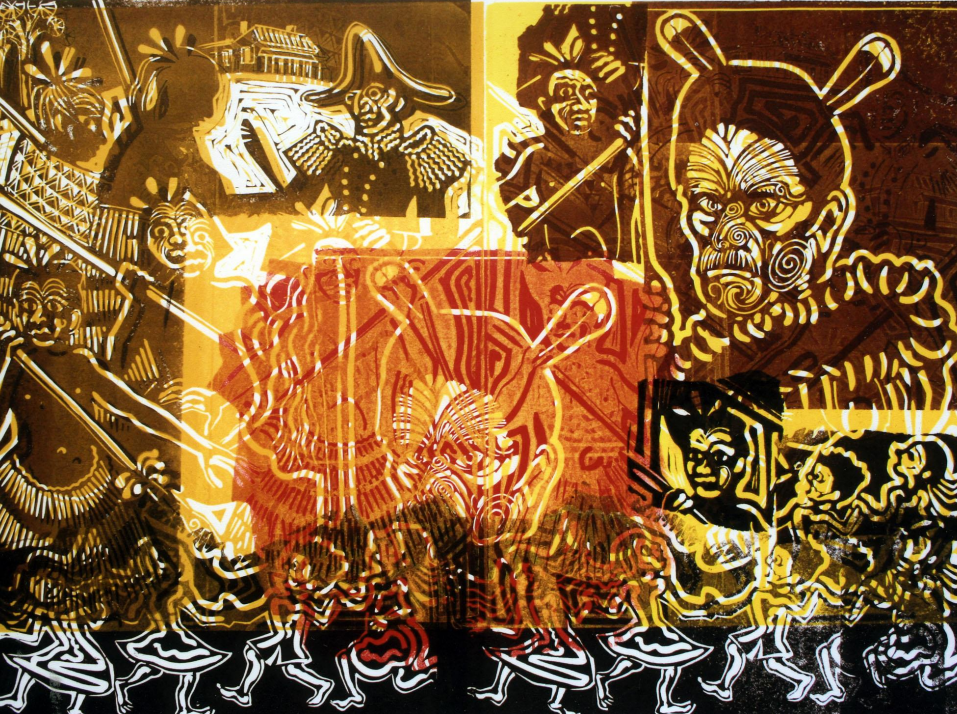

Painting away in his bedroom, Robert developed an allergic reaction to turpentine and some oil paints and had to seek an alternative way of working. He was visited at this time by the New Zealand artist, Don Peebles, who was to become the father figure of New Zealand abstraction, and a lifelong friend. Don urged Robert to explore the relatively new medium of acrylics, and at the beginning of the 1970s he created a series of large paintings using unprimed cotton duck and the techniques of the hard-edged abstractionists. He was never drawn towards pure abstraction and his tendency was always an unfashionable one, to tell stories. In exploring this new medium he took 19th Century paintings of Maori chiefs by the Bohemian artist Gottfried Lindauer and played in an abstract way with their shapes and patterns, and also created fantastic battle scenes.

Having given up his promising Fleet Street career for a period to paint, Robert was again forced to seek work in the early 1970s and for four years he became a government information officer, working in the Foreign Office News Department as Chief Diplomatic Correspondent, and travelling the world with Britain’s Foreign Ministers. He was sent to China and around Arabia, worked in the United Nations building in New York, took part in the first conference on European Security in Helsinki and travelled with James Callaghan to Kampala in Uganda to try to rescue from Idi Amin a British lecturer sentence to death for sedition. But he turned his back on this career too and in 1976, at the age of 41, he was admitted as a mature student to the postgraduate Royal College of Art, one of the few students accepted without a first degree. He was supported in this move by Professor Peter de Francia who was encouraging older students with unusual backgrounds to come to the Painting School.

Before entering the RCA he had embarked on a programme of psychotherapy and for the first time was confronting the considerable trauma of his early life. His three years at the RCA gave him the opportunity to explore these feelings in depth visually in works such as ‘Falling Airman’. After the RCA he returned once more to the etching department of the Central School and created a series of etching and drypoints which took this exploration further. By then he had become deeply fascinated by Jungian teachings and took up once again Paul Klee’s dictum to take a line for a walk, allowing his etching plates to become the stage for fantastical happenings driven by the unconscious.

These explorations came to an end in 1983, when Robert took one last dive back into the worlds of journalism and writing. He was commissioned by the publishers Jonathan Cape to return to New Zealand and to write a book examining the changes taking place in that society. He was particularly fascinated by the resurgence of Maori consciousness and Maori culture and in 1984 was invited by Robert Mahuta, foster brother of the Maori Queen, to accompany the Tainui Maori people on a great march or Hikoi, from Ngaruawahia in the middle of the North Island to Waitangi in the far north where in 1840 the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand’s founding document was signed. Maori from all over the country were marching north to put before the government and Crown their grievances over the Treaty’s broken promises.

On this Hikoi Robert became Robert Mahuta’s assistant, and framed for him the depositions which the Tainui people presented to the Pakeha authorities, and which eventually were to have a profound impact on government policy. At the end of the march he returned to Britain and wrote ‘The Fifth Wind’, a book which begins with an autobiographical description of his experience of New Zealand as a boy in the post-war years, and then looks at the changes which had taken place and particularly at the history of race relations, culminating in a vivid description of events on the Hikoi. The book was published by Bloomsbury and in New Zealand by Hodder & Stoughton and was illustrated by his own linocuts.

Much of the book was written in Wales, in an isolated cottage in the Brecon Beacons. It was a semi-derelict cottage discovered before he met her by his Welsh-born wife Annie, and after the publication of his book Robert returned there to make it his studio, and to paint the landscapes of the Usk Valley. He has lived in Wales ever since then.